No Manderaggio thorn

MINTOFF, MALTA and DIMECH

When well-known past events and personalities are visited by analysts who take up a perspective which is as subjective as much as novel the result is always exciting. No historical interpretation, however comprehensive, is ever the be all and end all. Viewed from different standpoints, our awareness of the past thus acquires a richness which is very often refreshing and even stimulating. For such contributions bring out hitherto unknown shades and assessments overlooked by others.

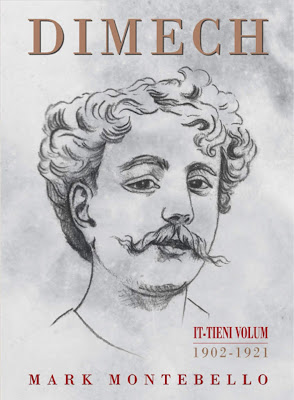

When well-known past events and personalities are visited by analysts who take up a perspective which is as subjective as much as novel the result is always exciting. No historical interpretation, however comprehensive, is ever the be all and end all. Viewed from different standpoints, our awareness of the past thus acquires a richness which is very often refreshing and even stimulating. For such contributions bring out hitherto unknown shades and assessments overlooked by others.Many parts of Dom Mintoff’s recently published memoirs, Mintoff, Malta, Mediterra: My youth, do just that. They are an historical document in themselves as much as a literary criticism worth consideration. It would be presumptuous on my part to even begin to attempt some thorough evaluation of the entire publication. What I propose here is to briefly inquire into just one chapter of the book, namely, that dealing with Manuel Dimech, the early 20th-century social reformer (pp. 57–102).

I must say, beforehand, with the most profound respect for Mintoff, that I do this solely for the sake of Dimechian scholarship with which I have been professionally acquainted for the last couple of decades and more. At present this learning has reached such a high level of expertise that it cannot allow sloppiness to go unchecked, especially when publications of a fairly wide circulation, such as Mintoff’s memoirs, are involved.

To begin with, I must state how thoroughly fascinated I found Mintoff’s view of Dimech’s niche within the framework of Malta’s then political and ideological spectrum. Mintoff endeavours to never lose sight of the larger picture and, as was his speciality, spot with considerable accuracy the shifting ground of political allegiances down to the minutest veer. His attitude is seldom if ever Manichaean, and consistently assesses each piece of the political strategy on its own merit, whether left- or right-leaning, and always in relation to context.

Seen through a long lens, Mintoff draws out a starker image of Dimech, one which seems to contrast more eloquently when charted within the political compass of his time. Of course, Mintoff does not hold back from projecting forward to when he was politically active some inferences extracted from Dimech’s thought and actions. Unsurprisingly, Dimech is thus portrayed as some kind of harbinger of Mintoff’s own times. (No harm in that)

Nevertheless, notwithstanding the merits of Mintoff’s chapter on Dimech, there are some faults which need to be signalled out lest someone might think that all’s well with it. I begin with the most glaring, namely, that Dimech was born at Valletta’s Manderaggio. He was not. Dimech was born at the opposite end in a tenement house in St John Street, wall to wall with the Ta’ Ġiesu church. As far as can be ascertained, Dimech never had anything whatsoever to do with the Manderaggio.

Though Mintoff makes this obtrusive misjudgement the linchpin of the entire chapter, he possibly could not have known better when he wrote his memoirs. He simply begs the question. For the relevant information concerning Dimech’s exact place of birth was not made known before the end of 2004 (Dimech, 2nd ed., vol. 1, 2013, pp. 43–6), and this was surely after the memoirs had been left unfinished. So much so that, however charming, Mintoff’s romantically-phrased expression, “Out of the Manderaggio thorn sprung the loveliest Maltese rose” (p. 63), at least in reference to Dimech, is completely incorrect. The chapter’s title, thus, identifying Dimech as “The Manderaggio thorn” is totally off the mark.

Many other minor inaccuracies and misjudgements pervade this particular chapter. For instance, from what is positively documented it is incorrect (or, at best, inaccurate) to state that Dimech “[became] an orphan when still a toddler” (p. 58; his first parent died when he was thirteen); that he grew up at Valletta’s “Diju Balli” (p. 58; he grew up at the outskirts of Qormi and of Birkirkara); that he embraced a “materialistic philosophy” (p. 58; it was pragmatic); that he “had never clashed with the law” before his 1878 manslaughter case (p. 60; he had gone to prison at least eight times already); that he was corrupted by “his companion [accomplice]” (p. 60; it was the other way round); that he committed the crime when he visited “a den run by a sharp card-player” (p. 60; he lived there); or that this “sharp card-player [...] cleaned [Dimech and his mate] of all their savings” (p. 60; no card-playing was involved, and Dimech and his mate were prey to extortion).

Also that, at his 1878 trial, Dimech “gave all possible help to his more experienced friend” (p. 60; he did nothing of the sort); that the priest who testified at the trial was “probably his devout mother’s confessor” (p. 60; she did not even know him); that Dimech was “almost six feet tall” (p. 60; he was four feet, eight inches tall); that in prison “two successive chaplains” were his friends and cared for him (pp. 60-2; only one was his friend; the other was his foe); that he “imparted [education] to other inmates” (p. 62; this never happened); that he “left for Tunisia to earn the means of outwitting and penetrating Malta’s ‘respectable’ society” (p. 62; he went to obtain a government financial benefit); that he was “encouraged by the English wing of the prison command” to declare himself a Protestant (p. 62; no such encouragement transpired); or that his 1891 incarceration was “his second term of imprisonment” (p. 63; it was his tenth).

Also that his beliefs were like those of “Voltaire and the Encyclopaedists” (p. 63; they were not; they were more like those of the British Empiricists); that he “gave private tuition to [...] foreigners” (p. 64; he only had Maltese students); that he was “bestowed the title of professor” by his students (p. 64; he gave it to himself); that in 1900 Bishop Pace celebrated a solemn mass at the Co-Cathedral for “Britain’s victory” over the Boers in South Africa (p. 65; it was for the 90th birthday of Pope Leo XIII, and his 22nd anniversary as pope); that for the same mass the bishop made “an unexpected exception [by inviting] many Protestant high officials of the local Imperial Government” (p. 65; it was neither unexpected nor an exception, but a matter of course); that Bishop Pace “condemned [Dimech’s] Bandiera immediately after its very first issue” (p. 69; the paper was in print for almost three years already); or that Dimech worked for “a free socialist republic” (p. 9; he had nothing of the sort ever in mind).

Also that Dimech “had his child baptized [...] at St Julian’s” (p. 79; all Dimech’s six children were baptised at Stella Maris, Sliema); that the Archbishop’s Curia is guilty “of the purposeful destruction of most of the official records [concerning Dimech]” (p. 83; they, and many other unofficial ones, are all at the Curia’s archive open for public study); that, during his excommunication, Dimech “resort[ed] to the publication of anonymous leaflets” (p. 83; this never happened); that Dimech’s stoning at Qormi happened “quite by accident” (p. 87; it was a prearranged pelting); that Dimech had “his home in St Julian’s” (p. 87; he lived at Sliema); that Bishop Pace issued the pastoral letter pardoning Dimech “fully three months after Dimech had signed his apology” (p. 92; it was just three days later); or that, when arrested before deportation, Dimech was “locked up in the Valletta police cell” (p. 95; he was kept at the Clistania prison in Merchants Street).

One must not discredit the whole of Mintoff’s book just because of the misjudgements in one particular chapter. This would be a grave mistake, and one certainly not intended here.

(Published in The Times of Malta, 23 November 2018)

Thank You and I have a nifty offer you: How Much House Renovation Cost Philippines house renovation and design

ReplyDelete